Extract: Nasty Women: Can the Goddess and the Hero Find a Way Forward?

by Mary Diggin, PhD

Published in Immanence, The Journal of Applied Myth and Story

To read the full article, visit: http://www.immanencejournal.com and fill in the contact form for access. The live version of Immanence has been suspended for now. Or email Mary for a copy.

During the final moments of the third and last 2016 US presidential debate, when Donald Trump interrupted his opponent, Hillary Clinton and muttered “such a nasty woman” into his microphone, he could not have foreseen how “nasty woman” would become a badge of honor for many women, uniting them in the face of perceived misogyny. The comment, as muttered by Trump, was intended to be a put-down of Hillary Clinton in face of a remark she had just made regarding the possibility that he may avoid paying increased Social Security contributions. Rather than being slighted, women began to embrace the phrase as a badge of honor. According to Emma Gray, #NastyWoman immediately began trending on Twitter. Within minutes of Trump’s comment, nastywomengetshitdone.com redirected to Hillary Clinton’s official website. Within an hour, Nasty Woman T-shirts were available for purchase. The phrase, to quote Gray, became “a viral call for solidarity (Gray). Even with Clinton’s defeat in the election, Nasty Woman remains a rallying cry for women throughout the States. Defined on blogs and on merchandise as a “confident independent woman who gets stuff done,” Nasty Woman has become a call to action in the post-election months (Nasty Woman Definition).

In opposition to the Nasty Woman meme, Trump drew on heroic ideals, portraying himself as the hero who would defeat the Nasty Woman and through doing so, “make America great again.” Bloggers like Ron Russell at Right Wing Humor rendered Trump as a modern-day Perseus who would slay America’s Medusa, i.e. Clinton. T-shirts available online showed Trump as Perseus holding aloft a beheaded Clinton-Medusa (“Trump Slays”). Trump supporters also drew on the hero motif in YouTube videos such as “A Hero Will Rise – Vote Trump Pence 2016” by eXZileXV. Paraphernalia such as t-shirts, buttons and mugs proclaimed “Trump is my hero” or depicted him as superman. Trump particularly drew on the mythologies of the warrior-hero who defends his homeland and its borders. His catch phrases of “Make America Great again” and “Americanism not Globalism” speaks to the focus on a homeland in need of defense, a homeland threatened by an enemy other, in need of its homegrown hero who instead of bringing battle out to the world, stands firm at his homeland’s borders and prevents occupation by the enemy.

Trump’s rhetoric, characterized by personal attacks and snide comments, can even be viewed as part of the heroic arsenal. Stylized verbal hostility was a common element in mythic encounters, involving boasting, self-aggrandizement, and belittling of opponents. Walter Ong noted in his seminal book Orality and Literacy that “[b]ragging about one’s own prowess and/or verbal tongue-lashings of an opponent figure regularly in encounters between characters in narrative: in the Iliad, in Beowulf, throughout medieval European romance, in The Mwindo Epic and countless other African stories…, in the Bible, as between David and Goliath” (43). Trump’s tweets and utterances can thus be understood as a manifestation of the heroic impulse, in the same manner as Achilles’ taunts to Hector in the Iliad, or Gilgamesh’s boasts to Enkidu.

In many ways, the social imaginary around the election drew on mythologies of the Goddess and the Hero, and particularly the goddess defeated by the hero. The proliferation of the image of Trump as Perseus, holding aloft the severed head of Clinton as Medusa, attests to how deeply embedded this specific mythic trope is in the culture. In general, for this article, I use the term “myth” to refer to traditional tales, prototypical myths, such as we find in Greek, Roman, and Celtic mythologies. I am interested in how myth operates in a cultural setting. As a metaphorical and narrative tool, I suggest that myths provide individuals and society a means by which they articulate about themselves and about the social world in which they exist. Myths can be seen as extended metaphors which allow us to imagine and re-imagine what is happening, and to open new possibilities by a creative engagement with images in myth. When a traditional myth, such as the slaying of Medusa, comes so strongly to the fore, and images a particular outcome, we need to heed it as a call from the world, a pointing to a certain energy and imagery that is particularly potent right now. When at the same time Nasty Women are also called forth by the hero-embracing Presidential candidate himself, we can perhaps read it as a cry for assistance, a recognition by the hero energy that it does not want to automatically fall into destruction.

Mythology has many nasty women like Medusa with her Gorgon head who turns men to stone, and Tiamat the great goddess serpent of Sumerian myth. These are the dark goddesses, mythic Nasty Women who are opposed and often defeated by the male hero, an iconography much drawn on by pro-Trump propaganda. Yet not all myths pose the relationship between hero and goddess as solely destructive. Not all goddesses die at the hands of the hero. There are other mythic possibilities, other ways in which the goddess and the hero can interact that may empower the Nasty Women of today and allow them find their way forward to work successfully with the currently ascendant heroic energy.

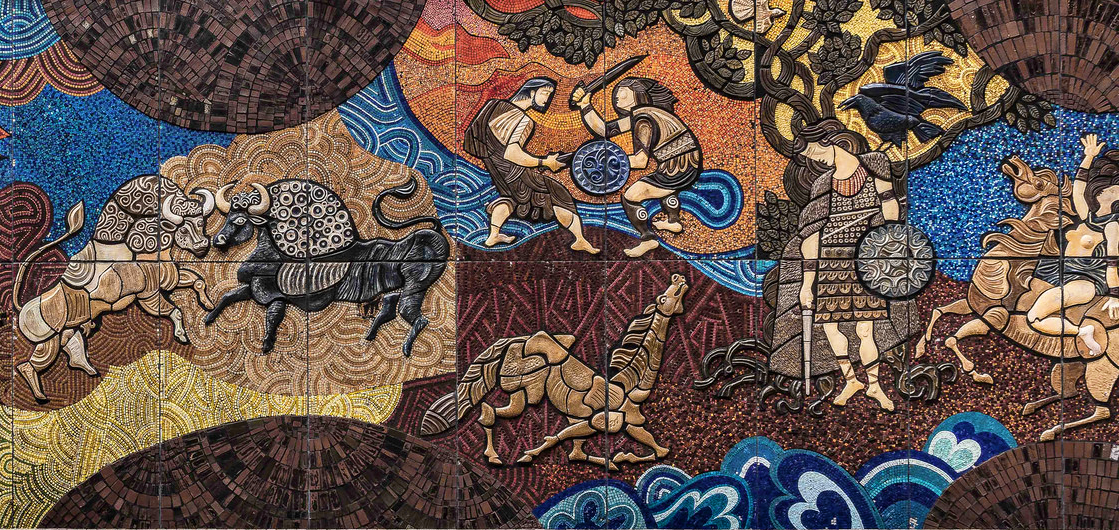

One of the supposedly nastiest women in mythology is the Irish war goddess, the Morrígan, a name that translates as Great Queen or Phantom Queen (Herbert 148,161). In the Táin Bó Cuailnge (TBC), The Cattle Raid of Cooley, the Irish epic tale, she interacts with Cúchulainn, the hero of Ulster, in the disputes between the Kingdoms of Ulster and Connaught over the ownership of the Brown Bull of Cooley (Kinsella 52-236). Unlike Medusa and Tiamat who are killed by their hero opposers, the Morrígan does not die at the hands of the hero. Instead, she offers him help and is rejected. The results are lethal: the death of his son, the death of his best friend, and Cúchulainn’s own death, years later, seeded by his actions in the TBC.

The myth may sound in some ways like a simple reversal of the Perseus myth, in that the hero dies rather than the goddess, but Táin Bó Cuailnge is complex in its portrayal of the relationships between the goddess and the hero, and between the hero and the feminine in general. While they are almost always opposed, their relationship swings from potential lovers to battling foes, and from injurer to healer, to name a few. It suggests that outcomes other than death are possible, if other choices are made. The TBC thus wonders about war and its causes, about men and women, about the nature of kingship and of warriorhood, of heroism, of love. The great hero of Ulster, Cúchulainn walks through the story and his interactions with the women of the TBC are core to the story’s unfolding. The most powerful women in Irish lore live in this tale: Emer, Scáthach, Aoife, The Morrígan. Mostly they are initially positive towards the young warrior, offering their encouragement and teachings. Yet at crucial moments in the story, Cúchulainn rejects the advice, offerings, or support of each and every one of them. Cúchulainn tells Emer as she pleads with him not to kill Connla, his son by Aoife:

Be quiet wife. It isn’t a woman that I need now to hold me back in face of these feats and shining triumph. I want no woman’s help with my work. Victorious deeds are what we need to fill the eyes of a great king. (Kinsella 44)

The rejection of feminine advice is one of the threads that weaves itself towards the conclusion of the tale, where death is supreme. The best and most beautiful of the warriors are gone. Cúchulainn has killed his own child and then his dearest friend by dishonorable means, and the two great bulls, the reason for the battle, lie dead in their fields. Cúchulainn himself is slain sometime later, as a result of his actions in the TBC. This is not a simple story of the wonder of war and warrior-ship, of glorying the great hero, but instead is a story of loss and death, of a bleakness of ending so complete, that one must wonder why and how it started, and what could have been other. Were other choices possible? Could the suffering have been averted? When the Morrígan sits as Badb, the Crow, awaiting the death of the warrior who refused to embrace her, it feels more like tragedy than victory.

A complex figure, The Morrígan is a war goddess who does not fight, a shapeshifter who flows between forms, and a raven who drinks the blood of the dead. The Morrígan is a triple goddess of the battlefield and originally the Goddess of the Land (Tymoczko 99-100). Like many goddesses, she has several functions and is linked to prophecy, fertility, death and destruction (Clark 228-9). The personas that account for her “triplicity” vary from story to story, with Macha, Badb, Nemain, and Anu all associated with her (226-7). She brings victory to the warriors with whom she makes love, as she did with the Dagda before the battle of Moytura (229). For those who reject her advances and advice, as Cúchulainn does, the results can be dire.

……

To read the full article, visit: http://www.immanencejournal.com and fill in the contact form for access. The live version of Immanence has been suspended for now.

Image info:

Detail from SETANTA WALL BY DESMOND KINNEY, Nassau Street, Dublin, Ireland, showing images from the Táin Bó Cuailnge: the Bulls, the battle between Ferdia and Cúchulainn, the Death of Cúchulain.

Photo credit: William Murphy, https://www.flickr.com/photos/infomatique/25535946264

Edited by Mary Diggin (cropped and color enhancement).